“The Newcomers” Is an Antidote to Anti-Refugee Rhetoric Invading Politics

by Jennifer Oldham

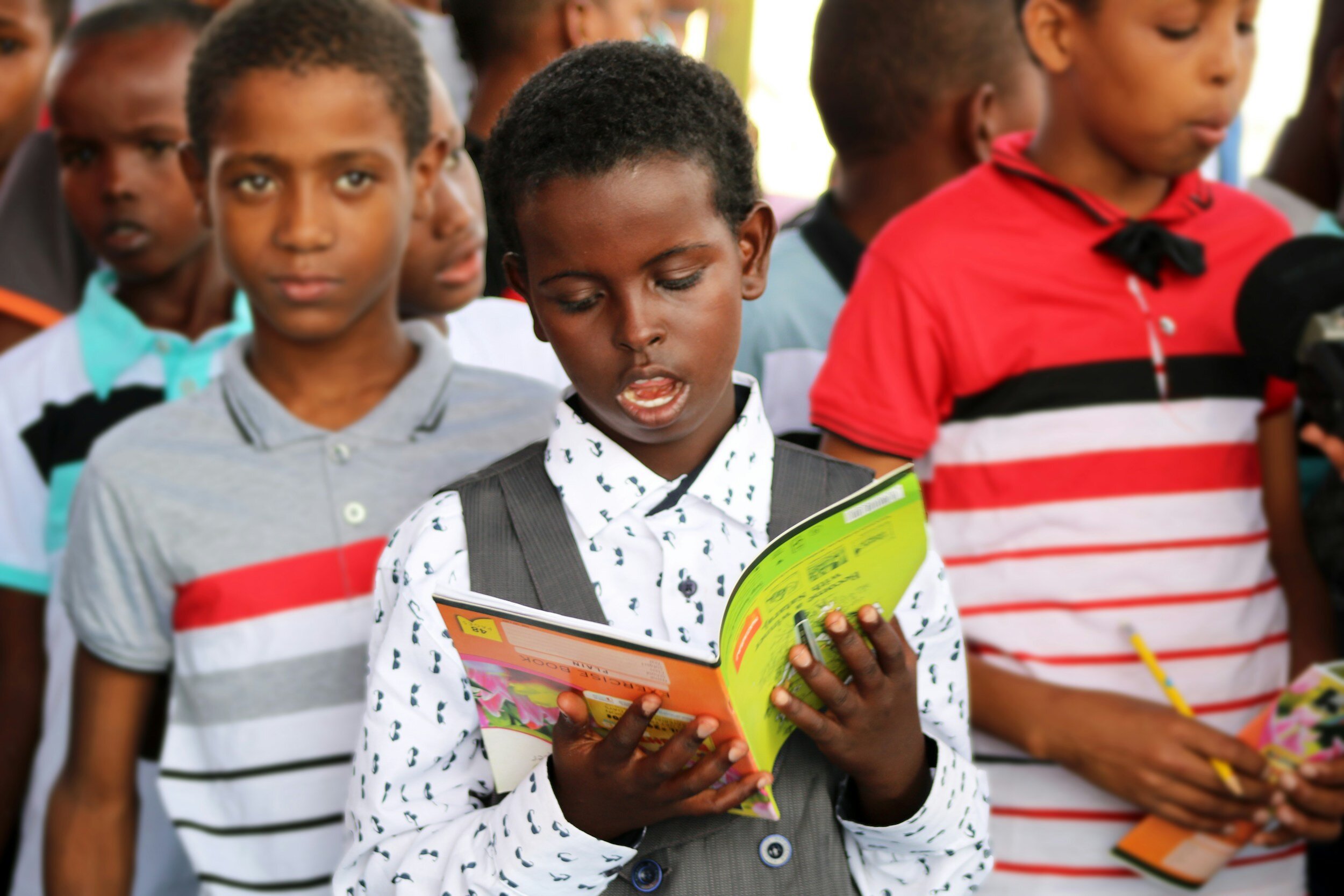

Photo by Ismail Salad Osman Hajji dirir, Unsplash.

The article was originally published in The Los Angeles Review Of Books ⸱ February 10, 2018

As the Trump administration prepares to allow fewer refugees into the United States this year than at any time in the 38-year history of the Refuge Act, Helen Thorpe’s The Newcomers: Finding Refuge, Friendship, and Hope in an American Classroom seeks to shift the nation’s polarized immigration debate away from viewing refugees as a burden and toward acceptance of their rich contributions to the United States’ culture.

In her third nonfiction work, Thorpe recounts the year and a half she spent with several dozen teenage refugees as they struggled to learn English at Denver’s South High School. With a student body that reflects the faces of the globe’s worsening refugee crisis, South High serves as a microcosm of the larger national debate over resettlement.

Thorpe follows the kids and their families through the resettlement process — with the 2016 presidential race as a backdrop — illuminating how difficult it is for refugees, many of whom never lived in apartments with lights or stoves, to assimilate.

JENNIFER OLDHAM: What intrigued you about refugees?

HELEN THORPE: My parents arrived in this country in 1966 with me when I was a year old. They are Irish. They emigrated first to England and I was born there in London. Then my dad got a job offer in the United States. A year later my mom had twins — the only American-born component of our family. I grew up here with a green card. My mom was always telling us stories about life on this dairy farm in Ireland where she was one of 10 kids. She had to do all the chores and, at one point, her dad even loaned her out to a sister of his who didn’t have any children so she could do all the chores on that farm. Her purpose in talking to us this way was to say, “Your lives here in America are a lot easier than the childhood I had — don’t take anything here for granted.”

South High School is Denver public high schools’ feeder for refugees. It excels in helping students master English and in Advanced Placement classes and is the school of choice for parents in the surrounding upper-income neighborhood. This is quite different from many urban districts where refugees are sent to schools in low-income areas that are struggling to ensure students graduate.

I really wanted to tell the story of English as a Second Language teacher Eddie Williams and the 22 kids he had, and the fact that they arrived here speaking 14 languages and using five alphabets, and his job is to teach them all English. It’s unusual that the English-language acquisition kids are celebrated to the extent they are at South and the way they’re integrated with the rest of the population.

How did Williams’s classroom help teach you about the world’s refugee crisis?

The Congo is the number one sender of refugees to the United States — four kids showed up from there. Burma is the second most frequent sender of refugees to the United States — two kids showed up from Burma. Iraq is next on the list — two kids showed up from Iraq. It’s really hard to empathize with the idea of what’s happening with refugees if you only discuss it at the macro level. It’s easier for people to empathize when they hear an individual story.

The kids’ ability to learn English revolved in part around their first language. You and the kids discovered surprising similarities between various languages throughout the year. Are Americans disconnected from our home language?

We don’t have to learn other languages as frequently as people from other places have to learn English. We are a little insulated from both the question of language acquisition, but also this whole question of how languages are interrelated. For me as a writer, that language piece of the book was so much fun. The kids could see I got delighted when they told me about cognates — similar words — they were finding between their languages. I just felt joy as a lover of words to be taught the similarities between Arabic and Tigrinya and Arabic and Swahili or Arabic and Tajik or Arabic and Farsi.

Most of Williams’s English students moved up at the end of the year, even though they all arrived with varying levels of proficiency. What was the essence of his teaching style?

One of the most moving, astonishing things to witness was Solomon and Methusella, two brothers from the Congo, learning so much English in their first year. They got to skip over a year and a half of English language instruction, and then halfway through their second year they started mainstream classes and started reading To Kill a Mockingbird.

One of the big challenges for the teacher is providing instruction at the rate his most proficient students are exhibiting as well as at a rate of, say, a kid who has been through traumatic experiences, or knows a language very far from English in origin. How do you accommodate all that in one classroom? In teaching, this is called differentiation, but it’s differentiation at a scale that’s even more extreme.

I’ll give you an example. Solomon and Methusella are in the same class. Methusella was 15 when he showed up; Solomon was 17. Originally Solomon had been ahead of Methusella in his schooling, but then he had to drop out of school back in the Congo to help the family with chores. Methusella got to stay in school. When they arrived in Eddie’s room, Methusella was ahead of Solomon. One of the comments Eddie made to me at a certain point was, “I am really noticing this must be a struggle for Solomon that his younger brother is ahead of him.” Solomon had never said a word about this. Not every teacher has this very incredibly attuned grasp for each individual in the room and what their personal struggle is.

You hired 14 translators to help you connect with the kids and their families. You wrote because of this you were worried you were hearing only an approximation of the story.

I put that in the book because that is all I was hearing. Was the interpreter always getting it a hundred percent correct? I think these interpreters work incredibly hard — many of them were refugees themselves. They completely understood the experience of the people we were interviewing so they could augment the interview and teach me as we were getting to know these folks. On critical information, we checked and double-checked.

You wrote that you saw the global refugee crisis in the room brought to life in a way you never saw represented in the daily papers. What do you think journalists were missing and are they still missing it?

In my reading of the papers I was getting a sense of the big picture, but I wasn’t getting a full appreciation for it at the individual level. What the journeys were and who were the people coming here.

This struggle to learn English that’s the cornerstone of building a new life here and participating in our society and becoming a full-fledged citizen. I just found it very moving to watch the students’ transformation from scared and overwhelmed at the beginning and unable to speak at all to flirting and making friends and having fights and making up and having sleepovers. The room became joy-filled and funny, with Saul from El Salvador proposing to Jakleen from Iraq in math class to Lisbeth from El Salvador chatting with Uyen from Vietnam about Converse high tops.

The students and their families escaped bombings, raids, and gang threats in their home countries. How did their experiences overseas impact their ability to adjust to life in the United States?

I wanted the reader to know about this, but I didn’t want to subject the kids to interviews that would be upsetting. I asked to meet their parents to let them tell me as much as they wanted about the families struggles and what they had endured.

The Congolese family didn’t want to rehash the traumas they had lived through — they wanted to focus on the present. They wanted to celebrate what was positive in their lives. They were happy to discuss with me in general the history of the Congo, but they didn’t want to tell me their personal stories of loss and violence. That’s why I decided to go to the Congo to try to understand the circumstances they had left.

In meeting the students’ families and watching them resettle here, what did you learn about the US resettlement process that isn’t understood by Americans?

We have this implicit idea that refugees are a burden. For the refugee families, this is the chance of a lifetime, to begin again, to find a safe home and have their kids thrive. The last thing they want is to be a burden. They become economically self-sufficient in this incredibly short time.

The agency that resettled the Congolese family found them an apartment, helped them navigate the US benefits process, provided them three months of cash and helped them look for work. At which point did you decide to involve yourself in the story?

When I started actually doing things like taking families on errands I checked in with my editor and said, “Am I allowed to do this? Because I feel like I’m crossing journalistic lines.” And he said, “You know what you are, but I feel like you are doing this because you are deeply moved. As long as you write about all of this in the book I think it’s great.” I wanted to step forward and be a little more transparent about the emotions I felt, and let myself participate more in the story; to help the kids in the classroom when they asked me for help, to bring families food if they were feeding me. I felt that the times called for this ultimately.

I think the whole game has changed — the game of journalism. The objective stance we work so hard to achieve can actually sometimes be off-putting to readers. They don’t know where we stand. I’m still trying hard to be fair, but I thought it was okay to be a little more subjective.

What myths did your time with these refugees and their families expose?

The act of wearing a head scarf — we have so many ideas about what that means that are not actually the whole truth. In this country we have a habit of thinking if a woman covers her hair that she must be Muslim; that she might be an enemy. When in fact all over the world, not just in the Middle East, many women cover their hair from various faiths. Christians cover their hair. Muslims cover their hair. I went to the home of a family from Eritrea and the mom had a head scarf on and I was like, “Oh, are you Muslim?” She said, “Oh no, I’m Christian.” She said the Muslims wrap the head scarf this way and I wrap mine that way. And I said, “You can read a head scarf wrapping. I don’t know how to do that.”

There’s a sense in our dialogue that refugees are to be pitied. Once I got to get to know them pity wasn’t the thing I felt. I felt awe. I felt admiration. I don’t know that I would be capable of holding it together psychologically if you plunked me down in a foreign country where I didn’t speak the language and told me to get a low-skilled job that was a little bit grim in terms of the nature of the work and be the sole breadwinner and have my son come home with homework that I didn’t know how to read and write because I didn’t know the language it was in. These people are amazing.

Did you mean for your book to be a call to action?

Let’s have a healthier dialogue about refugee resettlement. It does not need to be so fear-based. Of course terrorism is frightening. That is a distinct and different subject from refugee resettlement. In fact, refugees are fleeing terror and violence in their home countries. All they want is a safe home.

Let’s remind ourselves that we are very, very good at this. Five federal agencies vet all refugees. There is no instance in this country of a refugee committing a lethal act of terror. Some of the acts of terror that we are so concerned about happened in Europe, which has been admitting very large numbers of people without a formal refugee vetting process. It’s different from refugees in the United States. We don’t understand any of these distinctions.